Waldemar Ager and the Golden Age of Norwegian America

By Kenneth

Smemo

Professor of Scandinavian Studies, Moorhead State University at

Moorhead, Minnesota

-

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

- Introduction

- Ager's Personal History

- Editorship of Reform

- Ager's Career as Lecturer and Author

- Ager as Cultural and Linguistic Preservationist

- Ager as Temperance Advocate

- Ager as Founder of a Norwegian-American School of Literature

- Ager and the Politics of his Era

- Ager and Women's Rights

- The "Golden Age" of Norskdom in America

- Ager's Declining Years

- Conclusion

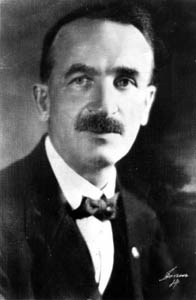

It has been said that Waldemar Ager may have been the most interesting Norwegian who ever migrated to America. Einar Haugen, that "grand old man" of Norwegian studies agrees, in his recently completed book-length study of Ager's fictional writings which will be published in 1989.

As an historian of Norwegians in America, I was first stimulated to investigate his career and his impact because of my childhood memories of him. Ager was an old man here in Eau Claire when I was a small boy and my father knew him quite well — and used to play whist with him regularly in the Sons of Norway Whist Club that was very active at the time.

Ager was still publishing his newspaper, Reform, at the time, but to an ever-shrinking subscription list, barely making ends meet in the Great Depression. As you know, Eau Claire and the surrounding area of northwestern Wisconsin was a region of quite heavy Norwegian settlement. But when I was small, in the later 1930's, there were only a few relics and reminders left of the thriving Norwegian-American subculture that had once been so alive here — and across the upper Midwest — only a few decades earlier. And Waldemar Ager's little Norwegian-language weekly was one of those relics — as was, in many ways, Ager himself.

Although I was only 7 or 8 years old, I remember accompanying my father to Ager's old-fashioned newspaper office and print shop on the second floor of a storefront building near the Four Corners on Barstow Street. I remember being impressed, as well as a bit intimidated, by that sprightly, witty, birdlike little old man with the sharp, penetrating eyes.

But he was very kindly toward me. He once gave me a slug of type from his linotype machine, which I treasured and played with long afterward. My parents had quite recently emigrated to America then and my first language of the home was norsk, so I was able to speak Norwegian to Ager. That may be why he was particularly pleased with me — for by then there were precious few small children whose mother tongue was Norwegian in Eau Claire any longer — or anywhere else in the Midwest for that matter.

In my adult professional life, as a teacher and historian of the Norwegian ethnic group in America, I've come to learn that the career of Waldemar Ager is not only interesting for its own sake. His energetic activities in behalf of his countrymen in America also illuminate, as the lives of few other important figures of the time can, the achievements, the social dynamics and the fragile texture of det norske Amerika in its most "golden age". That "golden age" of retention of the Norwegian language and culture in this land peaked during the decades from the 1890's to the 1920's — and Waldemar Ager was a central figure in making it happen. His influence was national — wherever there were Norwegians in ths land, far beyond just Eau Claire and northwestern Wisconsin.

He was born in Frederikstad in 1869 and grew up in Gressvik — just across the river Glåma. The street on which he lived there is today named Waldemar Agers Vei in his honor and memory.

In 1885, at the age of sixteen, he emigrated to America with his mother and two siblings to join the father in Chicago — who had gone to America earlier. Ager learned the printer's trade as an apprentice typesetter for Norden, one of Chicago's large Norwegian-language papers at the time. He also became an active member of a Norwegian temperance lodge there and began writing short pieces for its little monthly paper. He would remain a dedicated avholdsmann — alcohol prohibitionist — for the rest of his life — perhaps because of his father, who had drinking problems.

Ager moved to Eau Claire in 1892 when he was 23 years old. He had been offered a job here as a typesetter and fledgling journalist for a new Norwegian temperance paper called Reform. Upon the death of its editor in 1903, Ager succeeded to that position and eventually became owner of the paper; he would be associated with the paper for the rest of his life.

It was here in Eau Claire that he met a young immigrant woman from Trømso, Gurolle Blestren, whom he married. They were to raise nine children in the home he purchased on Chestnut Street — which still stands.

Reform became the main pulpit from which Ager pleaded his idealistic causes, urged his political opinions on his readers, and worked to raise the ethnic consciousness of his countrymen and women in the new land — as well as their moral and cultural level.

He shaped Reform into a highly personal organ. It became recognized by friends and foes alike as one of the most crisply edited and engagingly written, although often controversial, Norwegian-language papers in America. It never was a large, mass-circulated paper, but in the peak years of Norwegian language retention in America before the First World War, Reform had a respectable weekly circulation of some 10,000 copies. It was read by farmers, urban blue collar folk, and most of the people of prominence across the Norwegian American heartland from northern Illinois and Upper Michigan in the east to the prairies of the Dakotas in the west.

Reform became much more than just a temperance paper in Ager's hands. It informed, educated, entertained, berated, and, occasionally, no doubt, infuriated its readers. As in all of his writings, Ager's provocative style combined wry irony, clever satire and social criticism with wit, humor and a genuine folkevarme. A fellow author and journalist once described Ager as a writer who "had a lyre in one hand and a dissecting knife in the other".

Not surprisingly, the paper died when Ager did, in 1941, when its readership had declined to a few hundred old survivors of the Norwegian-American heyday that was now past.

Waldemar Ager was also a man of apparently inexhaustible energy. Aside from putting out his paper, he traveled widely and frequently throughout Norwegian America for forty years, speaking, organizing and working in behalf of his causes. He became a popular and well-known speaker who was much in demand throughout the Norwegian-American world.

He was a captivating and witty story teller at the lectern, just as he was in print, as he sought support for his beliefs in a persuasive and, obviously, highly entertaining way. He may have given at least a thousand speeches in his lifetime, and his platform appearances were as ubiquitous as was his little paper across Norwegian America.

Ager also found the energy and inspiration to write six novels and eight volumes of short stories, as well as occasional poetry. His creative writing was done at night, he commented once, when his wife and nine children were asleep and the house was quiet.

He also said once that he was eternally grateful for having been blessed with a good memory, an appetite for work, and little need for sleep. His career among his Norwegian countrymen gives ample testimony to the truth of this statement, as he labored tirelessly for over half a century in behalf of many causes whose common denominator was the retention of norskdom ["norwegianness"] in America. Although a short man of slight build, Ager remained a dynamo of energy and activity until his rather sudden death of cancer in 1941 at the age of 72. He was buried in Lakeview Cemetery in Eau Claire.

His great causes — the wellsprings for a life time of idealistic crusading — were three-fold:

First — and perhaps foremost — he was an ardent Norwegian cultural and linguistic preservationist. His dream, like that of a good many other Norwegian-Amercian leaders at the time, was to build a permanent Norwegia-American subculture within the larger American society. It would not be wholly Norwegian, but not totally American, either, while retaining the best in the Norwegian folk heritage. A bridge must be maintained between this Norwegian America and Mother Norway, he insisted, and that bridge was the language — the Norwegian language. When the language no longer holds, he wrote often, there will no longer be a bridge.

Secondly, he was a lifetime teetotaler who agitated passionately for personal abstinence among his fellow Norwegian-Americans and the achievement of total prohibition of alcoholic beverages. The temperance movement was broad-based and very popular among Norwegians in America, and Ager became a major leader and spokesman for the cause. He helped make temperance the most widely supported social reform issue among Norwegian-Americans and no single cause concerned them more. After the turn of the century, Ager helped found hundreds of total abstinence societies and Good Templar lodges across the upper Midwest — wherever Norwegians were clustered. My own research into the movement shows that it was much more intensive and pervasive among Norwegians in American than among the Swedes and the Finns, for example. And the Danes — like the Irish and the Germans — cared for it not at all.

Ager's third major goal was to encourage the creation of a uniquely Norwegian-American body of quality fictional writing — in the Norwegian language. There were dozens of serious writers, along with Ager, who worked at producing novels, short stories and poetry in Norwegian America in those years — including Ole Rølvaag, Simon Johnson, Dorothea Dahl, Jon Norstog, and many others. One among them would eventually surpass the rest and gain an international reputation for his work — that was Ole E. Rølvaag, the professor of norsk at St. Olaf College, and Ager's close friend. Ager's own fictional production is reckoned as being, on the whole, nearly as good as Rølvaag's best — and Ager was surely the most talented short story writer among Norwegian-Americans.

Ager was the first Norwegian-American writer to be published by a major publishing house in Norway — Aschehoug, in fact — when his novel of social criticism, Kristus for Pilatus, came out in Oslo in 1911. His major novels Gamlelandets Sønner and Hundeøine were also first published in Norway in the later 1920's. (Both of the last two are available in excellent English translations, should you want to sample Ager's fiction, but can't read it in the original: Hundeøine in English is called I Sit Alone. Gamlelandets Sønner was issued [in 1983] with the title Sons of the Old Country, translated by the late Trygve Ager, Waldemar's son, who also lived most of his life here in Eau Claire.)

These were his great driving passions to which he gave unstinting effort.

Ager also lent his support to a wide variety of liberal and even radical reform movements in the upper Midwest of his time, which sought to improve conditions for farmers and laborers. He staunchly advocated the progressive reform goals of Robert M. LaFollette here in Wisconsin, the cooperative marketing movement, and the socialistic Farmer-Labor Party of Minnesota, for example.

A scan of Ager's editorials in the first decade of the 20th century shows him also to have been consistently supportive of women's suffrage and equal rights for women. Such a stance set him apart from many other editors, public officials and Lutheran churchmen in Norwegian America. He was ever quick to publicize the rapid strides which the suffrage movement in Norway was making, ahead of the American one, where women had got the right to vote already in 1913 [U.S. women were enfranchised in 1920]. He urged Norwegian- American women to become politically involved, as women were doing in Norway, and he encouraged the growth of women's suffrage groups among them.

But the common threads that run through Ager's reformist impulses are those of democratic liberalism and moral improvement intertwined with Norwegian ethnic solidarity and cultural retention in America. He stood for bicultural pluralism within the American society, with political loyalty to the American nation and cultural loyalty to Norway.

Norwegian-American cultural and linguistic retention bloomed between the 1890's and World War I; Norwegian America was never more vibrantly ethnic — in dozens of cities of the upper Midwest like Eau Claire, and across the rural countryside, wherever Norwegians were clustered. Continuing mass immigration from Norway in those years gave a steady infusion of fresh Norwegianness to these older settlement regions which also helped keep the language and culture alive.

Over a million Americans used the Norwegian language in their daily lives in those decades: in their homes, churches and social circles — even often in their workplaces. Over 3,000 Lutheran church congregations used Norwegian as the sole language of worship and the readership of Norwegian-language publications was at an all-time high. Some 600,000 homes received at least one Norwegian newspaper in 1910, for example.

But despite the optimism for permanent language retention in this subculture, it was to be a short-lived "golden age" — shorter than Waldemar Ager or any of the other leaders of the group could have imagined.

The dream of a permanent Norwegian subculture in America was too impossibly visionary, likely, despite the arduous encouragement of preservationists like Ager, and would have slowly died out as successive American-born generations became increasingly Americanized. But its demise was greatly hastened by a new, national opposition to foreign ethnic retention among the native American masses after 1914. America's entry into World War I gave rise to the most wide-spread hysteria against non-English speaking minority groups that this country has ever seen. National campaigns for "100% Americanism", the censorship of the foreign language press, and a pervasive "Speak English!" movement hastened the end of Norwegian America in just a matter of years. German Americans bore the brunt of the intolerance of the times, of course, but the irrational national crusade against foreign cultures washed over onto Norwegian Americans as well.

Ager outspokenly protested the foolishness of it all, but he and the other leaders of Norwegian America couldn't stem the tide.

Into the 1920s, the maintenanceof Norwegian declined rapidly in every phase and institution of Norwegian-American life. The churches increasingly shifted to English, the readership of Norwegian publications dropped off sharply, and ethnic associations like the Sons of Norway and the bygdelags increasingly began to use English in their meetings — all to show the cultural loyalty to America that the larger society in this country now demanded.

Timorous Norwegian-American parents, in ever-growing numbers, now encouraged their children to Americanize fully — fearful that any signs of foreignness might stigmatize them in the larger American society and hamper their chances for future success in life.

The generation of Norwegian-Americans that came of age in the 1930's was almost totally Americanized — in speech, behavior and cultural attitudes. They were not only largely ignorant of the Norwegian language and heritage, but were often ashamed of this background as well. The "golden age" was gone forever.

Waldemar Ager lived on to witness his great causes disintegrate around him. Prohibition had proved a failure, Norwegian-American literature had no future since fewer and fewer could read it, and the language bridge to Norway no longer held.

But Ager remained a fighter to the end, as his writings show. Ager, furthermore, seemed to delight in a fight — even thought he knew it to be hopeless. He was, perhaps, too much of a Christian idealist and visionary — but he never became bitter over defeat, for he had the redeeming quality of seeing life ironically, with humor.

It seems to me that even though his great causes ultimately failed, he was not a failure. He lived life fully, exhuberantly, and purposefully — and seemingly took a great deal of pleasure in all his labors. He left a legacy of having tried to do his best for his people in their transition to a new land. His legacy is also an extraordinary body of writings, both fictional and journalistic, which attest to a time of heightened achievement and cultural creativity by the Norwegian people in America.

Which brings me back full circle to the spry little old man whom I met as a child. His heyday was behind him then, as was the Norwegian America in which he had played such an important formative role. Perhaps that boy from Frederikstad was the most interesting Norwegian who ever migrated to America.

— Speech given at Eau Claire, Wisconsin, May 15, 1988

Background illustration Syttende Mai i Chicago, by Emil Biorn, courtesy of

Nordmanns-Forbundet.

Reprinted by permission of Lizbeth Ager.